RIP Vojtěch Havel

Something about Little Blue Nothing and the desire for inner freedom amid repression

It’s no longer/ never was a career/ way of living, but being a music writer is primarily a thankless endeavor. Artists either ignore what you write or else hold a festering, decade-long grudge about a word choice in the sixth paragraph of a review that your editor inserted. My penultimate review for Pitchfork was a compilation of music from Czech couple Irena Havlová and Vojtěch Havel and it’s been so touching to hear from them over the years. They have always been thoughtful and considerate and the couple always reaches out to send me their latest works. Earlier this year, they sent me their beautiful new double-LP album, Four Hands, which finds them exploring piano and organ with their curious, ineffable practice.

At the start of October, I received a lovely surprise email from the Havlovis in the Czech Republic:

Dear Andy, how are you ? We are now on tour Four Hands, but we don't come to USA. It would be nice meet with you. Maybe sometime we will meet in NY or Prag or..... Many greatings. Irena and Vojtech

I meant to respond, but it was followed up a few weeks on with another email bringing sad news:

On behalf of the survivors, especially Vojtěch Havel's life and creative partner, Irena, it is my sad duty to inform you of Vojtěch's sudden death this Monday morning.

Please allow me to briefly address the many questions about Vojta’s passing. This message is written with respect for all who loved him, especially his wife, Irena Havel, who has agreed to share this information. I am grateful for the time spent with Vojta and Irena over the years, during which we connected on both an artistic and personal level.

Last weekend, Vojta and I traveled to the Faroe Islands, where we played two concerts in the intimate setting of local clubs. We thoroughly enjoyed performing and exploring this beautiful, mysterious country. Vojta showed no signs of health issues; on the contrary, he was in high spirits the entire time, energetically climbing hills with us and savoring the stunning views of the mountains and the ocean. He was looking forward to other upcoming concerts, including the launch of his new album *Four Hands* (Animal Music), which he recorded with Irena.

The last time we saw him was on Sunday evening when he got into a taxi at the Prague airport to head home. On Monday morning, after returning from a walk in the woods, he collapsed in his garden, and the paramedics who were called were unable to revive him.

So this post will serve as an homage to Vojta and his and his surviving partner Irena and their sublime pursuit of inner freedom.

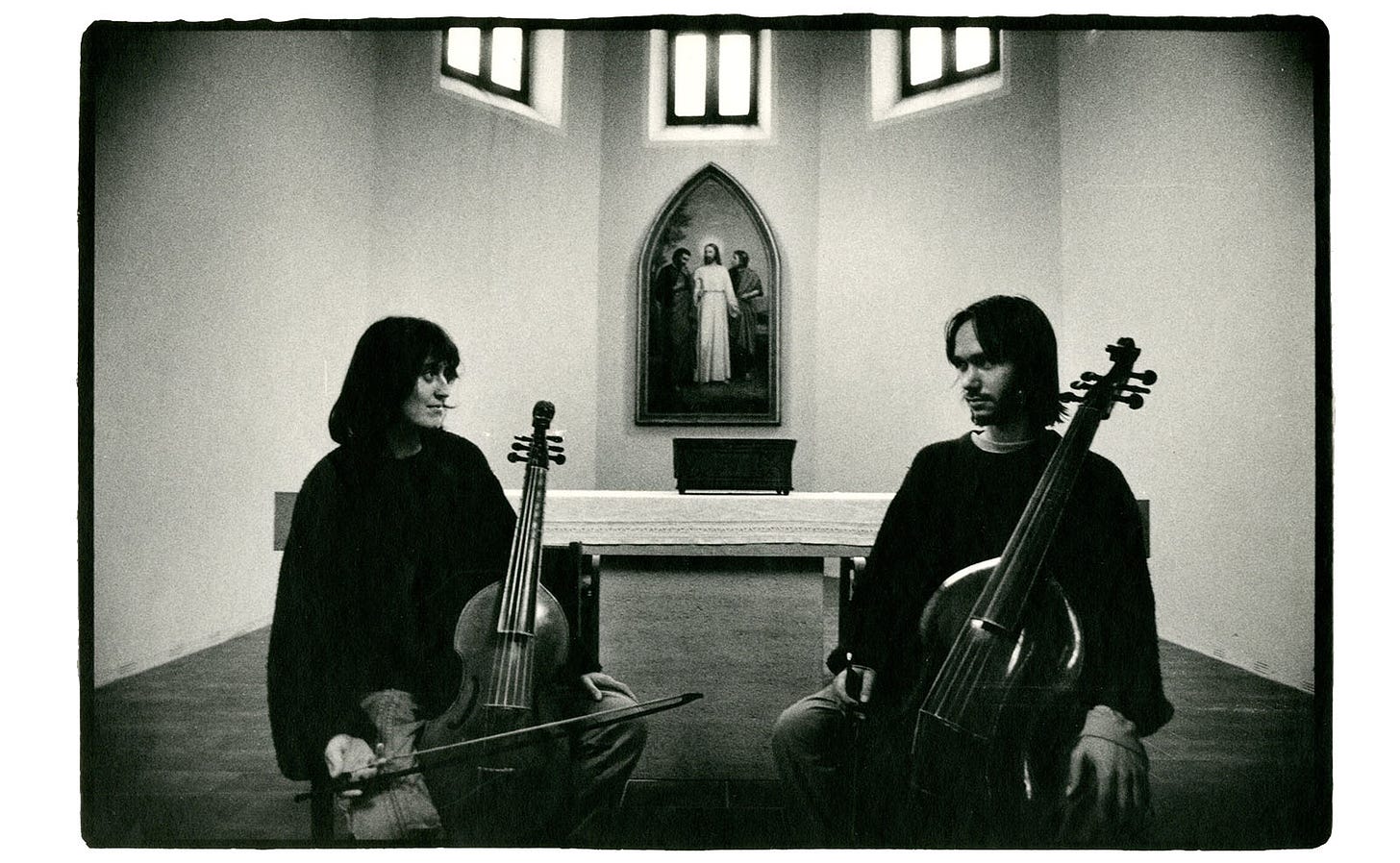

From the 16th through the 18th century, the viol, or viola da gamba, was so common that many affluent homes kept multiple specimens in varying sizes in a dedicated chest. The viol was eventually supplanted by other members of the violin family, although in the past half century, early-music specialists like Jordi Savall have contributed to a revival of the instrument. And in the 1980s, Czechoslovakian couple Irena Havlová and Vojtěch Havel also dusted off the viol to reconsider its long history within a modern context.

The Czechoslovakian couple have been playing their exquisite music since the ‘80s, music that is at once rooted in centuries-old tradition, yet also adventurous in incorporating new sounds and extended techniques. Over time, the couple quietly started garnering notice outside their home country. Vincent Moon, the director famous for his video series La Blogothèque, travelled to the couple’s home for his 2009 film, Little Blue Nothing. They found an unlikely champion in Bryce Dressner of the National.

“In the late 1980s my sister Jessica heard two Czech musicians, Irena [Havlová] and Vojtěch Havel, play in the street in Copenhagen,” he recalled. “She bought their only remaining LP and brought it home, and that is how I was introduced to the strange and lovely music of the Havels. Their haunting, minimalist patterns, played on the viola da gamba, are…inspired by the folk music of their native country. That record, Little Blue Nothing, was very influential for me as I started to compose music.” When Dessner collaborated with the Kronos Quartet for 2013’s Aheym, his piece “Little Blue Something” was rooted in the sound of the Havels.

“It took us years to realize we arrived on earth with a serene mind,” Havlová murmurs in Moon’s film. That might sound hokey if overheard at a yoga retreat, but seeing as the two grew up under totalitarianism in Czechoslovakia, it sounds like a coping mechanism—a way to find inner peace inside music, against a backdrop of state and social repression. Even when the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, paving the way for Czechoslovakia’s Velvet Revolution, followed by the flood of Western capitalism, the couple remained steadfast in their musical approach, as if outside the flow of time. As the couple put it on their website: “The only thing that can be said with certainty is that it is always music that is highly poetic, and penetrates the innermost corners of a perceptive human soul, enriching it at the same time.”

In this way, I think of the couple much like I think of John and Alice Coltrane, who used minimalist concepts like modal playing to express something universal. Rooted in something decidedly Eurocentric, they too found a way to incorporate the music of India and Africa and put it all on level footing. The Coltranes were steadfast in hewing to their beliefs and their personal quest for the universal, not deflected or distracted by exterior events of history. That example continues on in the Havels own discography, especially with regards to the couple’s travels through India in the early 1990s to study and play with local Rajasthani musicians, finding a common musical language with them and recording hours of folk and spiritual music amid their travels.

“Our desire to play is a desire of freedom,” says Havel in Little Blue Nothing. Across their discography, Havlová and Havel share an attuned and almost enviable telepathy, no matter their chosen instrumentation, which can feel spare and luxurious. But their viol duets—deep, empathetic, and also toe-curling—stand apart. At times, you might wonder if their music emanates from yellowed sheet music or perhaps some distant point in the 21st century, before shrugging and letting it just fill the room. That curious feeling of suspended time arises throughout their discography, in which three serene minutes can bring the entire modern world to a standstill.

Thank you Vojtěch and Irena for this exquisite music.