Felbm

Chatting with the Dutch artist about nature walks, micro-seasons, M.C. Escher, making and breaking patterns, and avoiding Vivaldi

I’ve been obsessed with the reissue work of Miles Cleret and his Soundway label for nearly two decades now. Since being hepped to the still-awesome T.P. Orchestre Poly-Rythmo The Kings Of Benin Urban Groove 1972-80 set, their Nigerian comps (and their Nigerian rock and their Nigerian funk and their Columbian and their Thai and their Brazilian and their South African comps, and also can’t forget their Nigerian boogie comp either) have all been illuminating, lovingly-researched projects. But the label has managed to release choice new music as well (think Bomba Estéreo and Ibibio Sound Machine).

But even then, there was something that felt different about Felbm’s cycli infini, released in 2023 and by that point his fourth release on Soundway. The work of Dutch producer/ musician Eelco Topper (Felbm is the result of an autocorrect of his name on an old cell phone), it was hushed, acoustic, minimal but highly melodic. At times its patterns would dissolve into field recordings, only to re-emerge again with new timbres, a new angle within the work revealed. It might suggest new age or jazz and then the patterns of classic Reich/ Glass, but one given over to the unfurl of nature, not allowing its rhythms –its human need for order– to get too rigid. And it worked as a whole, the music replicating the premise of its title.

Back in March, Felbm sent me a new work, winterspring/summerfall, released in conjunction with Objects & Sounds. It’s by far his most ambitious and most accomplished work to date, a fascinating amalgam of field recordings and melody, developed over a few years of observation and openness. At times, the music within seemed to echo some of my own recent sensibilities about the natural world and its seasonal patterns. When I reached out to Felbm, I had to confess something. Most times when listening to it while walking in Central Park, I would wind up just removing my headphones altogether so as to make sure I was hearing the birds in the trees overhead, the gentle gurgle of water in the distance. A compliment, to be sure.

I think I first encountered your music via 2023’s cycli infini, so I was startled to learn that you had an entire other music career making electronic beats as Falco Benz. Did you hit a wall with that project at a certain point? Or think, “this isn’t the way I want to keep making music”?

I think that during the creative process with Falco Benz, I had imposed overly strict limitations on myself (“use 4 on the floor,” “use synths,” etc.) that eventually stopped being inspiring and instead became paralyzing. There was a period when, while working on Falco Benz material, I was also preoccupied with what the audience or the music world might think of what I was making. By focusing on external factors, I lost touch with my internal source. This was one of the factors that led to creative and personal burnout symptoms, and at that point, I realized something had to change.

Another aspect that played a role at the time was that –alongside creating electronic music– I had always also been involved with acoustic or semi-acoustic music, more rooted in jazz. I noticed that I wanted to give that side of myself more attention and I also started to feel a bit too old to be making music for the dance floor—especially because I was increasingly seeking peace and calm in my own life.

What did you want to leave behind from Falco Benz and what would you say carried over from that project?

After reaching that point of burnout, I decided I wanted to spend less time behind a computer making music. So I bought a 4-track cassette recorder. I also began going to my studio (where my synths were) less often, and instead found myself at home on the couch, occasionally messing around with a guitar, accompanied by a very simple rhythm box. That’s how it really started: four tracks to capture an idea—a perfect limitation to keep from going overboard.

“Everything in life moves in cycles, and nothing ever truly disappears. That idea, combined with how I constantly encounter various patterns in my own life. Sometimes positive, sometimes negative—where you want to break out of them, but often end up in a new (slightly altered) repeating pattern.”

I grew up when doing “indie” guitar 4-track stuff was the thing before using computers. Did you have that phase before doing Falco Benz?

I didn't really go through a 4-track phase before I started working as Felbm. Even though it might have been something from around my time—or just before—I had an Atari with a Cubase MIDI sequencer when I was 16, along with a basic sample-synth that I used to make beats. The interest in working with cassette tapes probably stems from a youthful nostalgia for the sound of tapes. And in general, the sound of tape (rounded, warm) definitely relates to the kind of sound I’m looking for in my music.

One element that still overlaps between Falco Benz and Felbm is the classical structure of melody, harmony, and rhythm. This is almost always present in the music I make—actually quite traditional. The fourth element that always belongs in that framework for me is sound—how does it sound? That’s very important to me, and I think you can find similarities in that across all the music I make.

The inspiration for cycli infini comes from a fascination with how everything in life moves in cycles, and how nothing ever truly disappears. That idea, combined with how I constantly encounter various patterns in my own life. Sometimes positive, sometimes negative—where you want to break out of them, but often end up in a new (slightly altered) repeating pattern.

The idea (or insight) that everything moves in cycles has many layers. Some are obvious, like the natural rhythms of life and death, day and night, or the changing seasons. But it also applies to more (inter)personal aspects—entering and ending (and re-entering) relationships, sticking to daily routines, or going through a creative cycle where you make something, bring it to completion, and then begin the process anew.

On a personal level, for me it was also about the struggle with certain traits or behaviors that, over time, you realize aren’t serving you. So you try to change them. But often, after a while, I found that one pattern had simply been replaced by another—or a slightly different version of it—and that, when zooming out, I’m really just repeating the same loop again.

Compositionally speaking, how hard was it to make a piece that was cyclical like that?

It was definitely a challenge, especially in terms of maintaining focus. When I started, I had a rough sense of the outline and how I wanted to approach it, but I had never created such a long, continuous composition before—actually, quite the opposite. During the process, it’s also not that easy to quickly zoom in and out, since listening to the full piece each time takes a lot of time. So I had to constantly switch between those two levels: micro and macro. In the end, I just decided to trust that if I focused on the micro-level, the macro arc would naturally take shape—and that that would be OK.

Can you highlight a specific behavior or trait that wasn’t serving you?

One of my personal challenges is finding a balance between my natural tendency for control and the ability to let go. This urge for control often leads to unnecessary stress, which was one of the contributing factors to my burnout at the time. I try to learn from this, to practice, to take a step back. Sometimes, I succeed in finding that balance and manage to view the situation more loosely, but then inevitably, a new situation arises where I get stuck again in that controlling mindset, resulting in unnecessary stress (and the physical reactions that come with it). In those moments, I think, “Ah, here we are again.” And it feels as if I’ve hardly learned anything at all. These kinds of patterns, which are deeply rooted in your character, are difficult to break. In my experience, they can’t truly be broken, but you can adapt them slightly—hopefully for the better.

Was there something at the micro level that helped with the larger composition?

The initial concept for cycli infini actually started at a macro level, by placing small sketches along a timeline created by drone loops in a specific key. That was truly working from a “bird’s-eye view,” designing from above.

At the same time, I was working with the idea of metamorphosis, inspired by the works of M.C. Escher. Metamorphosis is, in essence, a series of small changes on a micro level that together shape the final new form. So I could also focus on small variations within a certain pattern, and as long as I kept taking steps forward, the bigger picture would eventually emerge on its own. In that sense, it’s a very logical progression—but it’s a different approach than starting with a full overview and then filling in the micro layer like a blueprint. In my process, I was constantly shifting between these two perspectives. Maybe there’s even a connection there with my urge to control versus letting go—learning to trust that if you just keep working on the micro level, the whole will unfold by itself, without needing to map it all out in advance.

With winterspring/summerfall, you again worked on a larger scale, perhaps with the biggest cyclical art work of them all, seasonal change.

I had been playing with the idea of creating something based on the seasons for quite a while, but I concretely began on November 7, 2022. Leading up to that, I had read about the nijūshi-sekki, the Japanese (and originally Chinese) seasonal calendar that divides the year into 24 periods of about 15 days. That seemed like the perfect framework to shape the kind of project I had in mind. It offered a tangible structure: a finer division than the four seasons alone, but not as extremely detailed as, for instance, the 72 micro-seasons that also exist in Japan.

Was the scale for winterspring/summerfall daunting? Was there a time in the process where the small details were eating you up, so to speak?

Since the calendar offered such a strong sense of structure, and I had learned (partly through the process of cycli infini) that working on a small scale naturally shapes the bigger picture, I now knew I could trust myself to intuitively keep a journal for each period, capture impressions, and translate them into musical reflections. You could almost say I’m breaking out of my own patterns! And in a way, I think that’s true: I’ve really learned to trust the process more and allow it to be what it is. A pure reflection—a time stamp, so to speak.

Where did you start?

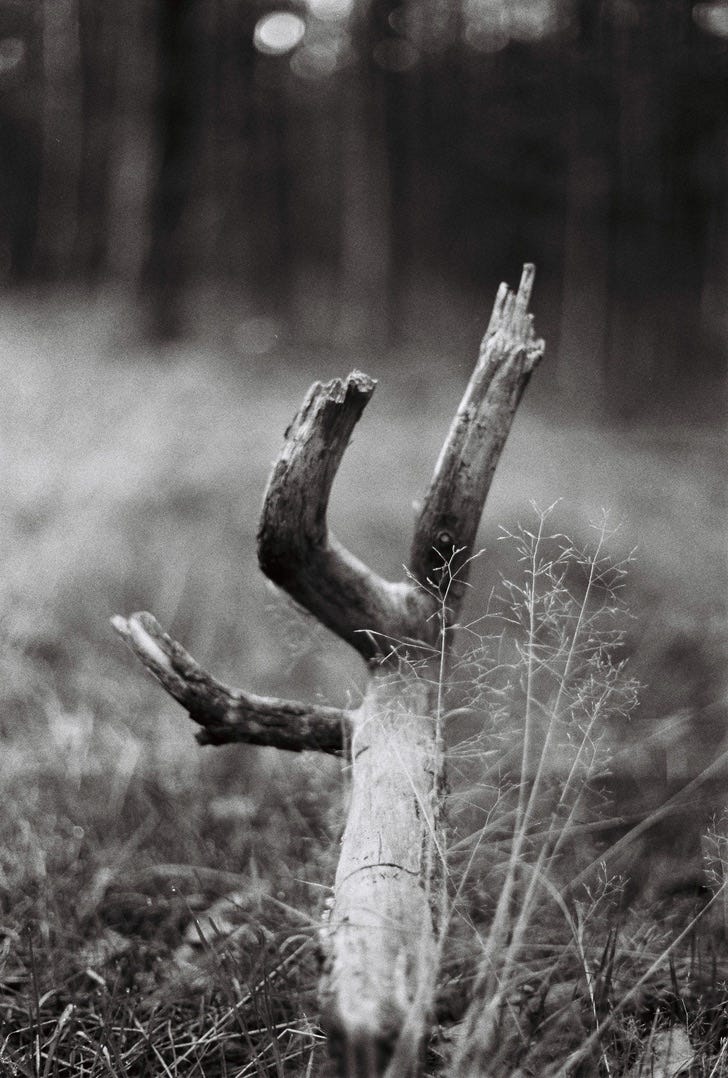

On November 7th, the beginning of winter in my calendar, I started keeping a journal of what I experienced in nature—mainly during walks in the forest. Alongside this, I took photos and made field recordings. This gave me a strong sensory impression of each period. At the same time, often at home, I created musical sketches—on guitar, piano, kalimba, and so on. This coincided with the season I was working on. At the end of that period, I brought all the musical sketches together and developed them into finished productions. That work often continued into the next season, during which I was already journaling again. So it became quite a literal and synchronized representation of my seasonal experience.

Interestingly, looking back, a lot of rhythmic patterns emerged during the winter episode—patterns that neither others nor I would typically associate with the feeling of winter. And yet, the root of those rhythms often lay in experiences in nature—wind and rain, for example, made the forest feel very rhythmic and energetic.

I’m struck by what you say about winter. Every day I walk through Central Park to my child’s school and in the past I just always thought of winter as bare trees, gray skies, cold cold cold. But this time, I started noticing the sky more and appreciating how the earlier sunset showed me these beautiful nuanced colors that I hadn’t really noted before. Did you find your own awareness shifting/ deepening as you went through the process?

It’s great to hear how winter’s charm opened up for you! I had exactly the same a few years before I started working on this project. By going for walks in the forest more often, I started to notice all sorts of small changes happening in nature, and I began to discover the beauty in them. Especially in winter—a season we usually turn away from more quickly; when we’re outside, we often want to go back indoors as soon as possible.

But once I started observing with this calendar as a guide, my experience of the seasons truly became deeper and more intense, because there was more focus on the subtle changes that occur every 15 days. And also because, for example, I deliberately sought out nature even in winter—walking, observing, listening—whereas before, I probably wouldn’t have paid much attention. Now I “had” to.

Where would you walk?

I mostly walked in two fixed spots in the Utrechtse Heuvelrug, a nature reserve close to Utrecht. Until a year ago, I lived in Utrecht, but I’ve since moved to a village in the Utrechtse Heuvelrug because I thought: if I’m going there every week to walk anyway, why not live there? It does me a lot of good to live so close to nature—and especially to the peace and quiet.

I deliberately chose to walk in the same places often so I could really notice the changes over time. So most of my impressions come from the same areas. But at the end of each season, I spent time working in (a total of three) different cabins in other natural areas, to process those impressions into musical reflections—to capture the season in music.

So the sketches arose from just walks/ field recordings and then the field recordings circled back into the piece?

Yes, that’s basically how it was.

What was the hardest season to assemble?

In fact, translating impressions into musical ideas went quite smoothly for each season. So the difficulty lay more in other aspects. I remember that while working on “Spring,” I started to feel a bit tired and saturated—or perhaps just empty. I had just finished “Winter” and was quite satisfied with it, but I noticed it was a bit much to have to dive straight into the next creative process (which had already begun by then).

The hardest, however, was probably “Fall,” because during the recording process I started experiencing a lot of physical strain from playing the flute. I’m not a trained flutist, and since I had decided to work with a very low (and therefore large) flute for Fall, I developed various aches in my hand, arm, and shoulder that didn’t go away. As a result, I couldn’t redo the flute recordings, which were initially meant as sketches. I had to accept that. And in the end, “Fall” may have become the most deep and layered of all. But it was definitely a painful season.

Were there other seasonal works that you spent time with or looked at? Vivaldi? The Beach Boys?

I realized only recently that there was an initial spark/idea when I was reading Karl Ove Knausgård’s Seasons series, quite a few years ago. Most of these are somewhat short / daily notations about observations in life. I actually stayed away from listening to Vivaldi. I don’t know why –I could or maybe should– have done that as research or for inspiration, but I felt that this project had to be my own authentic reflection of nature and the calendar, so I didn’t really look at other musical reflections of nature/seasons.

After the jump, Felbm talks about some recent musical inspirations, from an obscure likembi album to a beautiful jazz concert recorded out on the open water.