Blue Lake

A chat with Jason Dungan about his Texas childhood, giant empty parking lots, Garth Brooks' oppression, private music, and what's next for his Blue Lake project

In the way that a hot Texas day can create the illusion that a great body of water has materialized out on the distant, rippling horizon, it only seemed that Jason Dungan’s Blue Lake project appeared out of nowhere with his 2023 release, Sun Arcs. Since 2019, Dungan had been steadily carving out his own little soundworld in Copenhagen, where the Texas-born Dungan had relocated to (after stints going to college in Vermont and living in London). He self-released a string of cassettes and LPs, each bearing that vivid Yves Klein blue in its cover art.

A fellow Texan still processing the mythos of that forsaken land, while also embracing the freedom of spiritual jazz and life abroad, I was taken with the music itself, a heady blend of folk, ambient, minimalism, and jazz without being beholden to either. The music also clarifies Dungan’s curious space in music, somewhere between American cosmic guitar musings and the burgeoning Danish scene. (Also namechecking a sprawling live album by Don Cherry for your own project is also a great way to make my own ears perk up.)

Sun Arcs was where the insular solo explorations of Dungan and his hand-built zithers met the outside world, leading to strong reviews and the occasion to tour beyond Denmark to the EU and over to his former home. Enchanted by the new directions suggested on his latest EP, Weft, we traded a few emails about place, distance, and the lingering effects of a childhood spent down in Texas.

I realize we are both from Texas originally.

My parents moved to Texas in the ‘70s. Their intention was that they would only live there for a few years, but it ended up being 20. My father is a geologist and worked at NASA on the Apollo program, but we moved to Dallas shortly after I was born.

In Dallas, I took guitar lessons from a pretty skilled blues guitarist, who taught me probably the most important thing I ever learned about music. I was trying to learn a Jimi Hendrix song and was very focused on playing exactly the right notes, but the whole thing obviously sounded really stiff and boring. Then he played the solo and I realized the reason his solo sounded good is because he was playing with feeling. That stuck with me.

I also played cello in the junior high orchestra, my one and only introduction to some form of music theory. I loved the sound of the orchestra, particularly when we held a note together or when we tuned up. That sound of a whole group of acoustic instruments droning together was a huge thing for me.

My father did research out in southern Colorado every summer and we would drive back and forth, which takes 16-18 hours. He would make very meticulous mixtapes: a lot of Laurel Canyon stuff, but also Willie, Townes Van Zandt, and a lot of Talking Heads. The experience of those endless drives, looking out the window while the landscape slowly shifted, that was a big experience for me. Music and that landscape were a big thing.

I was recently back in Dallas/ Austin/ Houston to play some solo shows and I met up with an old friend of mine from the neighborhood. We talked about that time growing up there, which was very much pre-cell phone, pre-internet. Our group of friends was very into things like skateboarding and punk rock. I couldn’t skate to save my life, but we all hung out together and listened to music, watched horror films, and did slightly crazy stuff like investigate the Dallas sewer system with flashlights. My friend and I were reflecting on this time and how formative it was for us looking back on it. He makes films now and has even gone back to some of those places to use for his films. In Dallas then, the big music options were rock, country, and rap. And so if you were interested in other kinds of music or culture, punk was often the gateway.

Photo by Alex Kozobolis

Dallas has this double nature for me, where it can be kind of flat, monotonous, huge, lots of highways, giant empty parking lots. Those things felt both kind of boring and oppressive, but also at a certain point creative and exciting. An empty parking lot is an exciting place for a skater, for example. So in my early teens, it was also a landscape where we had a lot of freedom and could imagine different possibilities than what was immediately around us.

Did you leave Texas for college?

When I was 14, my father got a job in Geneva, Switzerland, so suddenly I was plucked out of Texas into a vastly different environment. I had always kind of dreamed of getting out of Texas, and I think that living among the conservative, religious culture there was quite heavy for me. Switzerland was very beautiful, also kind of boring, so I started just making music in my bedroom, recording things onto a tape recorder. Music at that point became a very intense, but slightly private obsession. And I think around then I started to think a lot about that legacy of growing up in Texas and that certain sounds, instruments, styles of music had stuck with me. In Switzerland at that time, there was a lot of techno and club music, so I didn’t know anybody who had those references or who liked some of that music.

I went back to the US for college, living in Vermont, where I got big into college radio, booking bands and also playing in bands. Around this time, I started to also think more about how these different moves in my life had altered my sense of music, and how it belonged (or didn’t belong) to a particular place.

I was reading something where you talk about the sound of the slide guitar and how normal and everyday it would be in Texas, but it takes on this exotic cast up in Denmark. Would you say Texas remains in your subconscious, if so, when you think about the place, what do you think about?

I’ve been in Denmark for 10 years now and I was pulled here by my wife, who’s from here, and also by the music scene in Copenhagen. When we were considering living here, I used to come to shows and was really blown away by the different scenes and artists here, as it really takes in everything. I had been making solo music for a few years that I called Blue Lake, but I hadn’t really released it. It was quite private.

What really impressed me in Copenhagen was that a lot of people were making really personal music and I started to think: what would my music be if it were really personal? I wanted to re-engage with the experience of growing up in Texas, where I had so many formative experiences with music. I love the sound of the slide guitar, but it was interesting to use it here, because it started to take on this element of pure sound, instead of being a signifier of country music. So I think that although I’m of course very conscious of these other musics and their histories, I also feel that I’m kind of exploring a personal set of sounds and ideas within this space of Danish music and culture, where there are simply different histories and associations. And that’s allowed me to both connect with that Texan/ American element in my music, but also to hear some of those things with different ears.

I miss things in Texas like the radio stations, where you can just tune in to a station playing Tejano music. I think I’ve also experienced the classic immigrant story by coming to Denmark, where the distance from something allows you to long for it, to create a relationship to it. I’m probably more interested in that legacy of living in Texas.

What does distance do to these seemingly familiar things/ sounds/ memories?

I think it amplifies and also rearranges things. I had a very tricky relationship to country music:I liked my dad’s Townes Van Zandt records, but that wasn’t the country music people were listening to in Dallas in 1991. Country music on the radio felt kind of like the antithesis of what I was interested in. It was Garth Brooks, George Strait, those kind of things that the evil bullies in my junior high –who would wear big belt buckles and boots– would listen to. So I was kind of afraid of those people.

Ugh, I know that fear well.

I think with distance, it’s not so hard to see how Willie Nelson and Hüsker Dü and A Tribe Called Quest can kind of coexist and interact musically (for the listener). And I think actually even just the sounds of things like pedal steel became more interesting for me when I was removed from that specific context and place.

Did the Blue Lake project begin after finding a zither in Sweden?

I think my response to the zither was kind of related to that idea of distance. I found an old zither in a flea market and the sound of all the strings together kind of clicked in my brain as something really exciting. But it was an old instrument, so I started building my own very simple instruments, just with an idea that they would be easier to tune and that the strings would be spaced more like a guitar, so I could play them individually more easily. Then I realized it sounded better with a bridge in the middle of the instrument, which also meant you could play two-handed, with a different tuning on each side of the bridge. So this started to encourage me to think about developing a playing style for the instrument.

By building my own instrument, it kind of allowed me to more freely explore how I wanted to play. It allowed me to evolve my own way of making sound on the instrument. Building the zither also allowed me to reconnect with the guitar, as it kind of refreshed my feelings about it. But I think it is also fascinating to create a little space of one’s own, just a small landscape which feels like mine.

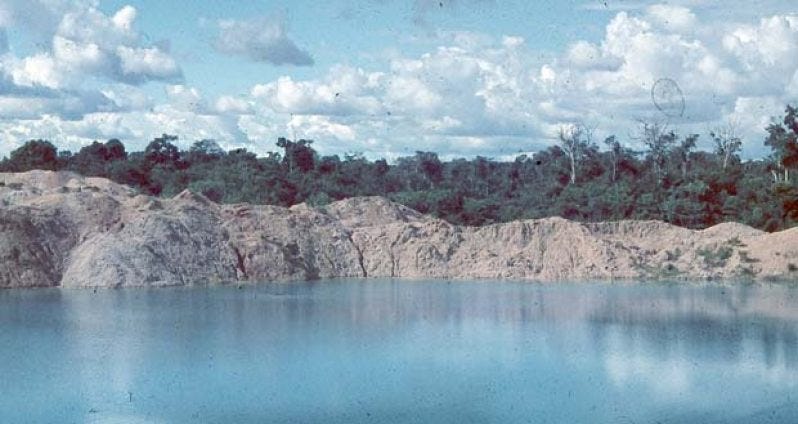

The real Blue Lakes of Guyana

Did the positive reaction to Sun Arcs surprise you?

It was definitely a big thing for me to have Sun Arcs connect with more people. I have been making music in various forms for many many years, often semi-privately, and for me the early Blue Lake records was really about trying to go as far into my own language, and my own feelings for making music. Not that the intention was indulgent, but rather kind of trying to connect myself as a maker of music with the person who is a lover of music, and really just trying to get as close as possible to the sounds that I hear in my own head, and to things that I love about music.

I had imagined Blue Lake as a passion project, with the original intention to play around in Denmark and connect with some record stores like Ergot Records in NYC, World of Echo in London, and All Night Flight in Manchester, who were early supporters of the early records. They also gave me a feeling that there were at least a few people out in the world who were into the music. I’ve had many years of making music –and also visual art– which had circulated more within my own circle of artists and friends. The feeling that there were people who were interested in the music was definitely a spur to keep pushing deeper into the project’s potential.

Before Sun Arcs came out, the music was already tending towards material that was more ensemble-sounding, more melodic and rhythmic. So after Sun Arcs came out, we played at Cafe Oto in London, a venue I used to go when I lived in the city, and where I have had many, many musical epiphanies at. We played a band show there and had a great response from the audience. This was kind of mind-blowing to me on certain levels. I had for many years thought of the music as a semi-private process. And yet, I have always loved seeing live music myself and being part of music as a communal experience. So for the project to exist on that level, where people were connecting with it, was really eye-opening in terms of what we could do as a live unit and what the music was capable of.

What direction is the music leading you towards now? Is it a bigger landscape? Do you feel heightened expectations?

Growing up, I was into rock music. And within that world, there was often a feeling that bands had a lot of pressure to follow-up a record if it did well. This leads in some ways to a kind of strange culture, where bands wait years to make a new record due to pressures / fears over living up to the previous record. I’ve been quite inspired by the jazz / experimental world, where there’s often a lot less pressure on the individual record and people just keep working and making new music.

Weft really was the feeling was that I had a group of tracks that would work well as a 30-minute record. It was a way to document the new things I / we had been working on in the immediate era after Sun Arcs and it felt good to record that as its own thing. Once Weft was finished, I started writing and demoing new material that would be more collaborative and that record would have its own sound and feel.

So over the past 8 months, this landscape for the project has definitely widened, both in terms of developing some new pieces in collaboration with the band members and also getting into the possibilities of using a recording studio, which creates certain possibilities and allows us to get a bigger, more textured sound.

This means embracing the idea of being a band leader, where I can guide and steer the music in a direction, but where I also give over elements to the other players in the band. So it’s been a process of both embracing new possibilities, while also trying to hold on to the elements of my solo writing and recording process that I feel are important. Even though I’ve been recording in a studio, I’ve been trying to adapt my home-recording process to the studio environment. In the process, I think the music has taken on a more direct sound and at the same time we’ve been using the studio environment to shape the music in ways which aren’t possible live. I’m really excited about the new music that’s coming out of the process – it feels like a natural progression and also like something really new for the project.

Read on for a little bit more about Dungan’s recent listening favorites:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Beta’s Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.